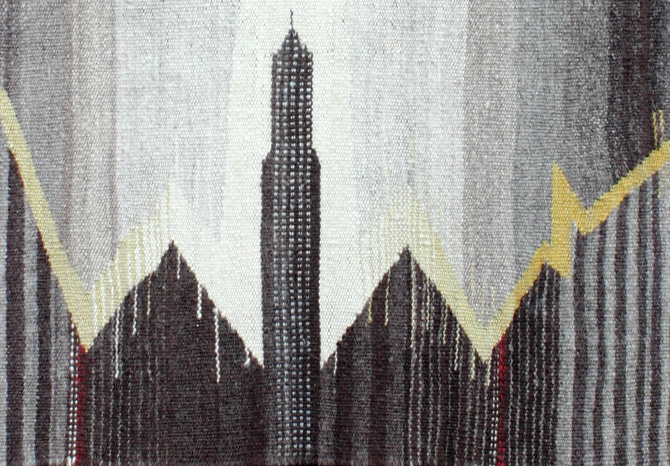

Detail: Storms© |

A Magical Medium |

Stanley Bulbach's art work reflects our origins as well as our current times. The roots of the carpet making arts in the Near East arose primarily out of the need of people to protect themselves from the harsh elements. When the earth upon which people lay down was cold and hard, carpets provided insulation and made that ground more comfortable. One need only imagine life prior to the availability of chairs and frame beds to appreciate how crucially important these weaving traditions were to basic survival. And when people developed the ability to include designs in their carpets, they were able to imbue ideas, wishes, protective magic, and even a sense of homeland in these portable life-improving surfaces. For thousands of years in the Near East it was on carpets where people slept and dreamed, where they prayed, made love, conceived, and gave birth, where they convalesced when ill, and also where they died. Carpets like these became the special surfaces upon which life's most important events transpired, and over time, this gave rise to the traditional patterns and designs used in the creation of these traditional pieces. In considering the designs, it is important to understand the important role played by the nature of the wools and the woven structures. It is virtually impossible to create a carpet without some kind of a design manifesting itself in the weaving process: It is virtually impossible to weave a field with the traditional materials that appears purely monochromatic. Even where the area might appear to be homogeneously the same color, it usually has significant variations of reflectivity. It probably did not take very long for the carpet making skills to begin to develop specialized designs, not only for decoration, but for the artistic powers to assist in the transformation of the ground beneath the carpets into special places. Thus, in carrying a carpet from place to place, at the end of one's travels one could then lay the carpet down and magically recreate a comfortable place with its familiar special powers. Therefore, when creating a carpet, not only were traditional weavers creating an important utilitarian object, they were also creating an aesthetic piece of spiritual importance. Could any artist — ancient or contemporary — seek a more expressive and exciting canvas than this woven metaphor of the human condition? |

|

Detail: Fall Too Soon© |

In his work artist Stanley Bulbach creates woven pieces based upon three different types of Near Eastern carpets: prayer carpets, carpet beds, and flying carpets. Each speaks to a different type of human consciousness. Furthermore, his work incorporates abstract designs as well as more representational ones. And just like the classical art form does, his work too also reflects urban imagery as well as natural imagery. One of the most familiar classical Near Eastern carpet art forms is prayer carpets. In this tradition, carpets are used to transform the ground into a familiar space reserved for prayer. Traditionally, these carpets can have designs that point towards a special direction and can have design elements that seem to be focal points. Like meditation, prayer is an alternate state of human consciousness. And in his prayer carpets the artist includes design elements reflecting these elements. For example, in the prayer carpet, "Fall Too Soon," the large snowflake is the focal point of prayer and meditation. |

|

Detail: Horse Chestnut © |

One of the most common traditional uses of carpets in the Near East has been for sleeping. In his carpet beds, Bulbach weaves designs that reflect the support on which the sleeper goes to sleep to dream, which is yet another form of alternate consciousness. For example, in "Salix," one would sleep under a willow on the soothing surface of a cool spring with spirits below. |

|

Detail: Crisantemi© |

While flying carpets did not exist in reality, they did exist in Near Eastern lore. For his flying carpets, Bulbach typically includes imagery that imparts a strong sense of movement often towards another dimension, sometimes implying a sense of the erotic or death or rebirth. For example, in "Crisantemi," Bulbach alludes to a famous funerary composition by Giacomo Puccini. Butterflies alight upon chrysanthemums, but in a way that suggests that the butterflies might be migrating through openings in a dark screen into a brighter dimension. |

|

Detail: Night Hawk© |

|

In the Near East the carpet arts actually draw deeply upon two dissimilar traditions at the same time, one urban and the other rural. That is because the traditional carpet arts were developed and maintained both in the cities and in the countryside and cross-pollinated each other. Bulbach's art work reflects this dual nature too. For example, in "Night Hawk," where wild life soars against a pattern of lit windows that create a three dimensional sense of the sides of tall buildings.

|

Detail: Heat Lightning© |

Therefore, not only does Bulbach's art work reflect three types of traditional carpets — prayer, bed, and flying carpets — and abstract designs as well as urban and rural types of designs, his art work also builds upon the special nature of the wools used, the classic natural dye palette, and the very special and abstract nature of the structure of the flat woven technique. And the special sensitivity to the special materials used and the special flat woven structure, adds the aesthetic considerations familiar to many from oriental art forms. All of the elements and considerations are orchestrated together — truly interwoven — to create the final art work. And as each of these elements is discovered and appreciated by the viewer, additional dimensions of magic and meaning can then be enjoyed. |