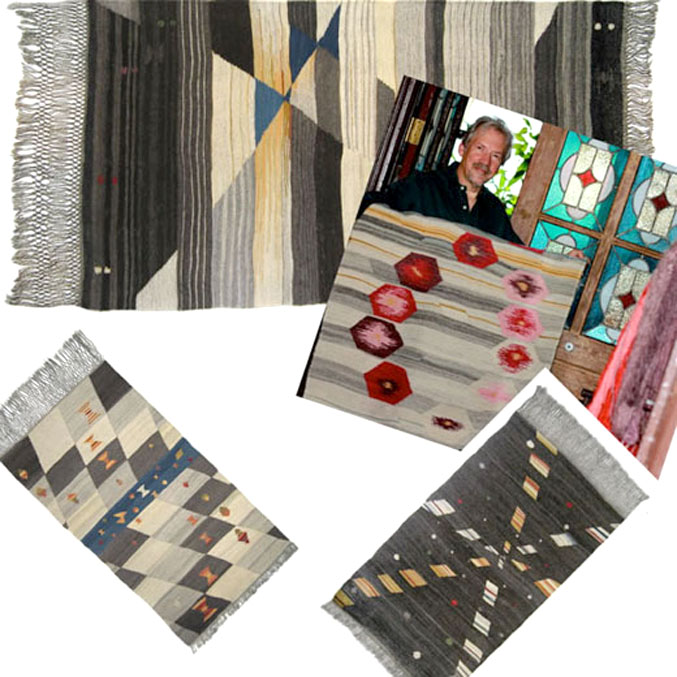

| Photo: by Sam Spokony , ChelseaNow |

Bulbach Weaves Ancient

Craft |

|

Longtime artist and neighborhood activist Stanley Bulbach has lived in Chelsea four decades — having moved, during the February blizzard of 1969, into his apartment on West 15th Street (where he still resides). His home is also his studio. Bulbach's material, however, is not paint, wood or stone. Instead, he works with fiber - handspun into yarn and woven into abstract compositions rich in symbolism. To some, these works may be described as rugs or carpets — but "wall paintings" would be a more accurate definition (they are works to be appreciated while mounted on the wall as contemporary art). Because he works from home, the size of his apartment determines the scale of his loom — and, consequently, the size of his works. Bulbach came to his work by way of history and philosophy. He holds a Bachelor's degree in the History of Religion and earned his MA and his PhD in Near Eastern Studies at New York University (specializing in the ancient Mesopotamian roots of our civilization). In the course of his studies and in particular during a trip to the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, he encountered the art of Classical Near Eastern carpet weaving and was struck by the medium's artistic expressiveness and inherent cultural significance. Over the years, Bulbach has acquired comprehensive knowledge of his materials, which he sources and prepares with utmost care. He has found suppliers of quality wool, has turned an old bicycle wheel into his spinning wheel, has educated himself about pigments and dyes and has learned that his materials can be "cranky and willful and do not always behave as planned." Meanwhile, Bulbach divides his work into three general categories: flying carpets, bed carpets and prayer carpets. Within these chapters, compositions have shared characteristics (prayer carpets always feature a distinct focal point, for example). While these compositional concerns seem painterly, Bulbach makes a clear distinction. "The real magic of this art form," he states, "is not recreating what painters can do. The real magic for me includes the original functions and understandings of these traditional carpets." Though consciously following a historic tradition, Bulbach has succeeded in providing his work with a contemporary context. In particular, the buzzing frenzy and architectural characteristics of New York City have found their way into his compositions. In "Sixth Avenue" (a prayer carpet), Bulbach transforms the city into abstract geometric shapes. The palette ranges from grays and off-whites (the natural colors of the wool) to blues and yellows. There is a mathematical quality to the interplay of verticals and diagonals, which reflect the dramatic light changes caused by towering city buildings (the sidewalk level remains dark while the tips of the buildings are catching the morning sun). A similar effect dominates "Times Square" (a flying carpet), in which crisscrossing banners of light describe the nocturnal convergence of busy avenues, bright windows, advertising signs and rushing taxis. To Bulbach, his work is often a contemplation of home, an outlook ingrained in the Near Eastern tradition. "To the nomads, who treated them as special surfaces, rugs signified the home you remembered," he explains. "People slept on these rugs, making them places of dreams." They also used them for prayer and at times as deathbeds, transforming the rugs into stepping stones to the afterlife. Bulbach's "September Passages, NYC" (a flying carpet) shows a dreamlike sequence. Falling leaves indicate the nearing chill of the season, as does a swarm of migrating Monarch butterflies headed South. The scene takes place between Manhattan's glass towers — and despite all abstraction, the viewer can sense the tension between manmade structures and nature. While Bulbach's subjects are eclectic, a distinct sense of stillness runs through all of them. Be it snowscapes featuring oak trees in winter, a depiction of the Third Sephardic Cemetery in New York, storms, solstices, slate puddles, night hawks or morning glories, Bulbach's compositions are cohesive in their stylistic and emotional impact. This consistency of tone might be partially explained by the fact that he contemplates each composition for a long time, allowing ideas to manifest. He completes only a handful of works each year. When discussing the genre of fiber art, Bulbach is quick to point out its lack of art world recognition. According to most galleries, museums and curators, weaving is considered a craft — not an art form. Despite their artistic expression, carpets or rugs cannot avoid being viewed as functional objects. Meanwhile, the fiber field avoids entering the debate. In contrast, Bulbach pushes for explanations. In an article written for the newsletter of the American Tapestry Alliance, he asked what he views as one of the fiber field's most important questions: "Why does the contemporary art establishment assign a lower hierarchical importance and value to woven imagery than to painted imagery?" To change this stigmatization, the fiber field will need more visibility and unity. For now, the limiting label for Bulbach's genre is Contemporary American craft art — which, not unlike folk art and outsider art, remains a grey zone. Bulbach, however, is not one to shy away from debate. For years, he has actively criticized the absence of communal support within the field. While there are several trade publications (to which Bulbach contributes regularly), fiber artists lack a strong voice in proclaiming why the works they create are indeed art and of cultural importance. To Bulbach, his chosen medium functions as a metaphor. "Weaving together divergent opinions and concerns into successful solutions for the community's challenging problems in New York City is often similar to weaving together the somewhat wild long wools and natural dyes into a finished carpet," he explains. His passionate viewpoint extends towards many community causes. At the time of the Vietnam War, Bulbach volunteered as a "draft counselor" for the American Friends Service Committee at the Quaker Meeting House on East 15th Street. He was the head of the Tenants Committee for the Old Law Tenement building he lives in from the early 1970s through the mid-1990s. He was a longstanding board member of the Chelsea Housing Group, the Chelsea-Village Partnership, and the Armory Action Association, as well as a founding member of Citizens for Union Square. Since the early 1990s, Bulbach has been the Chair of the West 15th Street 100 & 200 Block Association, which has addressed issues ranging from deeply entrenched drug and gun dealing, to subway access, smoke and noise pollution, robberies, murders and burglaries. Bulbach adds, "Over the years, many people volunteered and worked together on these issues. Many of them are no longer here. But the improvements they contributed, to make Chelsea what it is today, are bittersweet. The community is now one visited by the entire world. But in many cases, this process of improvement has also pushed many of them out of this community and they are sorely missed." The experience of Bulbach's work is two-fold. While a viewing from a distance provides an overview of each composition, its varying forms and palette, a close inspection reveals the impressive amount of detail involved. As the eye narrows in on the minute characteristics of the fiber and the structural organization of the weave, one begins to experience the interconnectedness of the involved elements. Bulbach has gathered and fused them into a unified front. Considering his passion for the community and for bettering the world around him, it is hard to imagine a more befitting art form for his creative mind. ©2011 Stephanie Buhmann. |